Fashion Nova and Racism in the Fashion Industry

By Hannah Schmidt-Rees

Racism is present in every aspect of our society, and is evident in many different forms. Now, I will admit, I am not one to completely comment on the racism in our society, I have never experienced it, and I never will. I can never understand what it’s like to be discriminated against or unnecessarily threatened just because of the colour of my skin. But, I have a platform, and regardless of how small that platform is, I have a responsibility to talk about how racism is present in an aspect of society that I will probably spend the majority of my life in; the fashion industry.

Like I said before, racism is present in every aspect of our society, and fashion is absolutely no exception. Fashion has always been tied to elitism, as well socioeconomic status. The origin of the fashion industry began in the Victorian Era, which led to the hierarchy that favoured white designers, based in Europe. This hierarchy has continued to today, regardless of how accessible fashion has become to all parts of society.

Much like the majority of history, black history is often overwritten by white history, even if an aspect of history is originally created by black individuals or people of colour. This is the most evident, for fashion with hip-hop fashion, athleisure and luxury streetwear. In the 1980s and 90s, hip-hop became one of the most influential music genre and cultural movements, originating in the economically struggling African-American community of South Bronx of New York in the late 1970s. By the 1990s, the East/West Coast rivalry, the influence of gang activity and the inclusion of of violence in certain songs led to a media-fuelled perception that hip-hop was a dangerous underground culture, further fuelled by the underlying racism within the USA.

The African-American community throughout history have used fashion as a tool to manufacture an identity that was both; better fitting of the their cultural identity, or better fitted to be accepted by the white-dominated culture around them. Fashion is a major aspect of an individual’s identity, especially those in subcultures of societal minorities. It provides those who have a restricted autonomy by society, control over how others perceive them. In a life of disenfranchisement, one experienced by many African-American citizens in first-world, predominantly white countries, fashion is used as a joyful rebellion; to present yourself as someone who is unaffected by the underlying racism in your community.

The unique look of hip-hop artists created a visual subculture, creating smaller cultures, including; streetwear, sneaker culture, luxury streetwear and looser silhouettes. A single music genre led to a growth in African-American led businesses and personal ‘brands’, creating success in areas of economic struggle.

Decades after its rise to fame, luxury brands continue to reference hip-hop or other black-created subcultures in an inherently racist and elitist method; often appropriating black designed works without credit or aspects of black culture in a predominantly white context, while also creating a ‘glass ceiling’ for black members of the fashion industry.

Daniel Day, also known as ‘Dapper Dan’ is a Harlem-based couturier, often known as the “king of knock-offs”. Making his name in the 1980s and 1990s, Dan provided those in the hip-hop culture, garments with a unique blend of gangster-inspired style and high-end luxury goods. Once gaining popularity in the early 90s, luxury labels sued Dapper Dan for violating copyrights, leading to the shutting down of his own store in 1992.

In 2018, Gucci created a jacket design that was highly similar to Dan’s 1989 jacket made for Diane Dixon, leading to a public outcry over appropriation of a black designer’s work without credit, especially because the garment was displayed on a white model.

The majority of dominant fashion trends now were created by black artists and designers, subsequently stunted by major brands at the time, then capitalised upon by the same brands without credit or compensation.

Cultural appropriation occurs when a member of dominant culture takes a cultural element of a minority culture without consent, attribution or compensation. Black students are often shamed for wearing their natural hair, or in a style that reference their heritage. Black hairstyles are oftendeemed as ‘ghetto’ or not viewed as traditionally ‘beautiful’. However, luxury brands style white models in black hairstyles in order to look more ‘urban’, disregarding the culture behind them. Comme des Garcons, Marc Jacobs and Alexander McQueen have all shown examples of cultural appropriation on their runways. This is a clear example of the white elitism in fashion, proving it difficult for black designers to comfortably express their black culture through their work.

Less than 10% of 146 designers at the last New York Fashion Week were black, and only 15% of the 7,608 models that walked in NYFW were black.

In a corporate yet creative industry, black individuals face a ‘glass ceiling’, a racial barrier that denies them access from reaching the top tiers of the fashion industry, especially in an industry where their culture is appropriated and reduced to a simple aesthetic. Inherent racial discrimination in the fashion workplace further racial stereotypes that discourage the future of black design from following the ‘traditional’ path into fashion design, especially in a vastly white dominated industry. Many black designers choose to create their own labels instead of working for a pre- existing brand, creating a path that isn’t inhibited by racial discrimination or racial barriers. Aurora James of Brother Vellies and Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss are examples of black designers deciding to create their own brands.

Through the evolution of our society within the past decade, instances of cultural appropriation are frequently called out by the public, especially in the current climate in which public opinion can ‘make or break’ a popular brand. In addition, the racial barriers are slowly being broken by the growing number of ‘woke’ individuals and companies in the fashion industry, as well as black individuals using their own careers to pave the way for their predecessors. More black models are being featured both on runways and in editorial/magazine shoots. Black designers and black- owned fashion brands are being highlighted by online publications, including InStyle and Teen Vogue. After Gucci’s Dapper Dan appropriation scandal, Gucci teamed up with Dan to create a capsule collection inspired by his archive, as well as an atelier and making Dan the face of their #GucciTailoring campaign in 2018.

This teaming up was part of Gucci’s charge to “unify and strengthen our communities across North America, with a focus on programs that will impact youth and the African-American community”. There is evidence of a changing fashion climate, however is this simply evidence of change on a surface level?

With the rise of fast fashion and particularly the exposure of the rights of fast fashion’s workers, the underlying racism is reinforced by the imagery of black individuals (predominantly women) as sweatshop workers, while their white counterparts are within the higher tiers of the business. The conditions that these black workers endure; low wages and poor working conditions; are unethical and unfair with racial undertones. Whilst the slowly rising number of black designers and models featured in the current fashion industry demonstrate progress, the ignorance towards black workers conveys the opposite. In addition, the whitewashed references to black culture on runways continues the vicious cycle of underlying racism and damaging stereotypes. In order to demolish the racial barriers in the fashion industry, changes must be implemented in all aspects of the industry. If the fashion industry genuinely changes, a precedent will be created, further encouraging the rest of society to alter their perceptions of those who are different to themselves.

Representation matters. If black entrepreneurs/students/designers etc. see themselves in the success of other black designers already in the industry, it shows them that success is achievable in an industry that is perceived to be biased based on race. Success stories like Virgil Abloh and Olivier Rousteing are history making moments, showing black excellence and black history to the highest degree. Whilst putting a black designer at the top of the fashion ‘food chain’ is highly significant, it simply isn’t enough, as diversifying all ‘layers’ of the industry will truly transform the industry for all those involved, changing the inherent views currently held.

In the cases of the still frequent racist scandals by luxury fashion brands, the quick and persistent response by the online community creates standards and boundaries to keep brands aware of the consequences of appropriating black culture and black work. The pressure by society on brands to be more diverse in their workplace/staff and through events with runways/models essentially forces brands to be more inclusive with achieves the end goal of creating a viable path for future black designers. In May 2019, Abloh posted images of his Off-White team to his Instagram. His image of Off-White’s art directors was called out for its lack of diversity, as all the directors were white. This issue is especially important for Off-White, a black-owned brand. However, the issue of diversity does not solely rest on Abloh’s shoulders, regardless of the fact that he has a highly influential place in the industry.

Every fashion brand and fashion employee have a personal and professional responsibility to open up opportunities for diversification. Regardless, as a designer, Abloh understood the difficulty of being a black designer in the pre-existing industry and created Off-White to make his own name in a very ground-breaking and successful way. His expression of black culture and diverse representation in models shows his pioneer spirit to dismantle the whitewashed stereotype of luxury fashion, but it’s clear that in order to make a fundamental difference, that pioneering spirit needs to be applied to all inward and outward aspects of his business, including his art director team. There are plenty of upcoming black art directors that more than capable to join the iconic brand.

Another incredibly important part of racism in the industry is through product development. Much like the instance with Gucci copying Dapper Dan’s work and presenting it without credit on a white model, there is still evidence of brands copying the work of black designers, cashing in on the design while stunting the original designer’s growth.

A big example of this is the brand that’s taking over the online fast fashion world; Fashion Nova.

Fashion Nova was the most searched fashion term in 2018. It’s also been successful win working with incredibly influential celebrities, including Kylie Jenner and Cardi B. But the truth still remains; Fashion Nova: trash. Not only do they only promote the same aesthetic; the curvy yet thin, ethnically homogenous vision of femininity (something I’ve touched on here), they have an extensive history of selling knockoffs of black designer’s work.

Luci Wilden, of brand Knots & Vibes, discovered that Fashion Nova was selling a direct knockoff of one of her crocheted dresses, even down to the number and placement of stripes on the garment. Upon this discovery, Wilden contacted Fashion Nova, only to be replied with the excuse that one of Fashion Nova’s vendors (the production company that Fashion Nova buys designs/products from) was responsible for the copy, not Fashion Nova themselves. There’s absolutely no way that Fashion Nova would be completely unaware of the designs they were buying from these vendors. They have certain trends to fulfil to stay relevant, so they must be aware of the designs they’re choosing. The design was sold out, but Wilden didn’t receive any compensation.

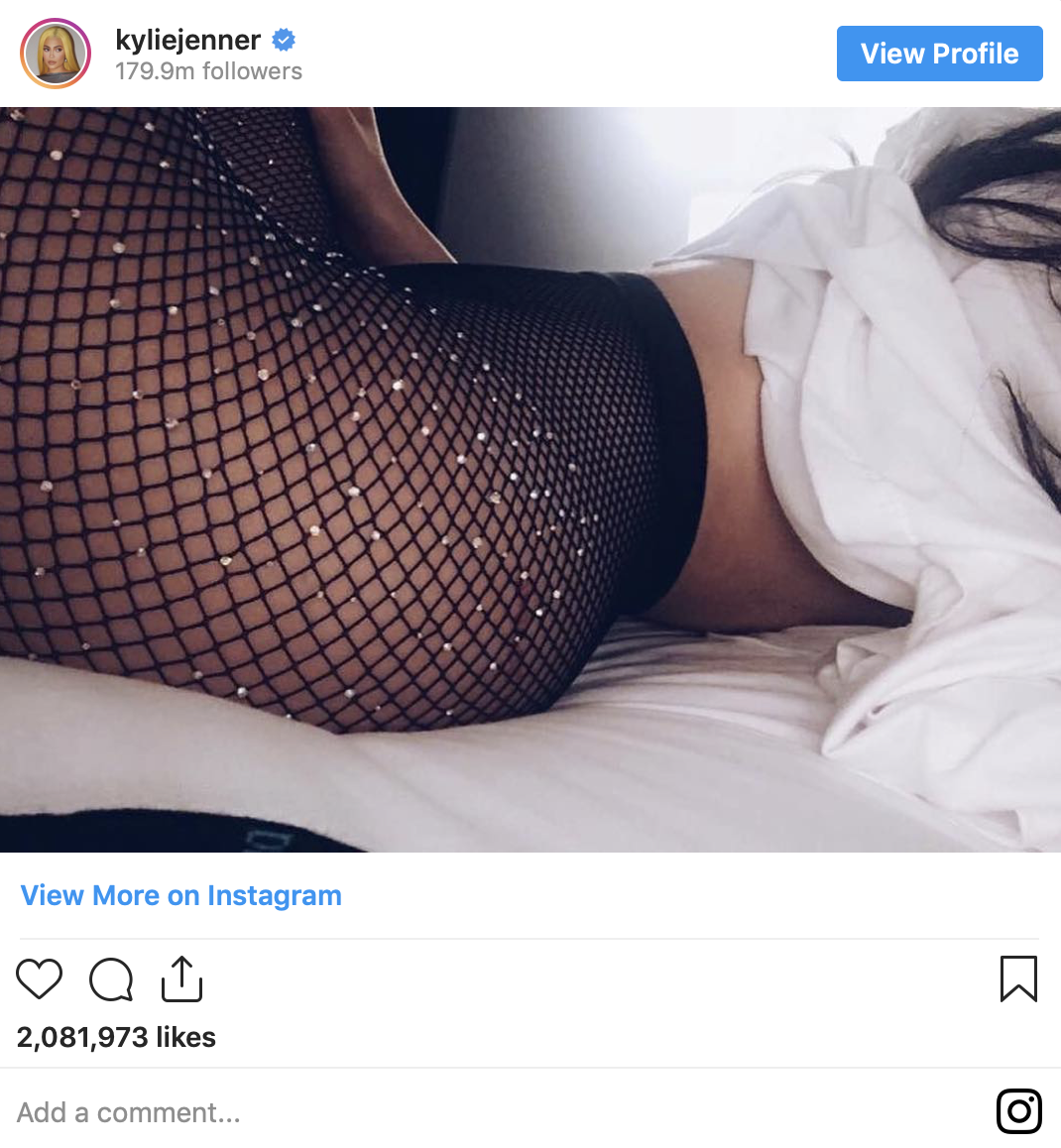

Another case is Destiney Bleu, owner of d.bleu.dazzled. Her signature crystal-encrusted tights (once worn by Kylie Jenner) were copied by Fashion Nova, (and other indie brands subsequently) causing a $100k drop in her business. Bleu created outfits for Beyone, Lady Gaga and Shania Twain, her work even being featured on the TV series Empire. Kylie Jenner posts an image of her in the bleu.dazzled tights, which is an amazing feat for Bleu’s business, but Fashion Nova starts to release a cheaper version of the tights,, promoting them with the same image. This obviously causes brand confusion, preventing Bleu from solidifying her brand. Fashion Nova’s version of Kylie Jenner’s image was taken down, but they still sell the knockoff tights on their website.

In addition, Fashion Nova has also been accused of not posting black models or black influencers on their website and Instagram page. Also, with the only black model they did employ at one point in time, Atim Ojera, she was underpaid and was only employed to be the brand’s sole black representation. Ojera fulfilled her contract and vowed to never work with Fashion Nova again.

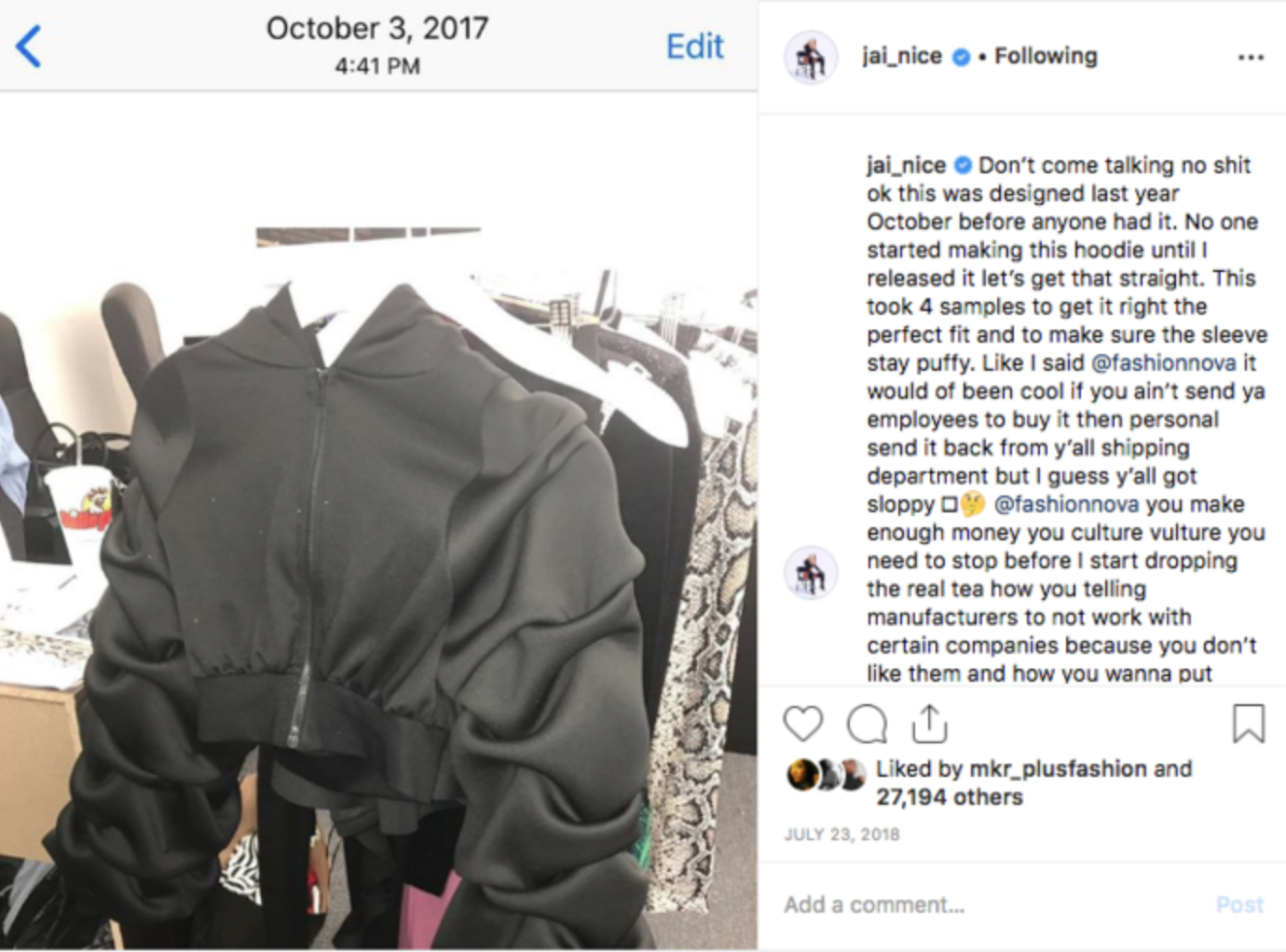

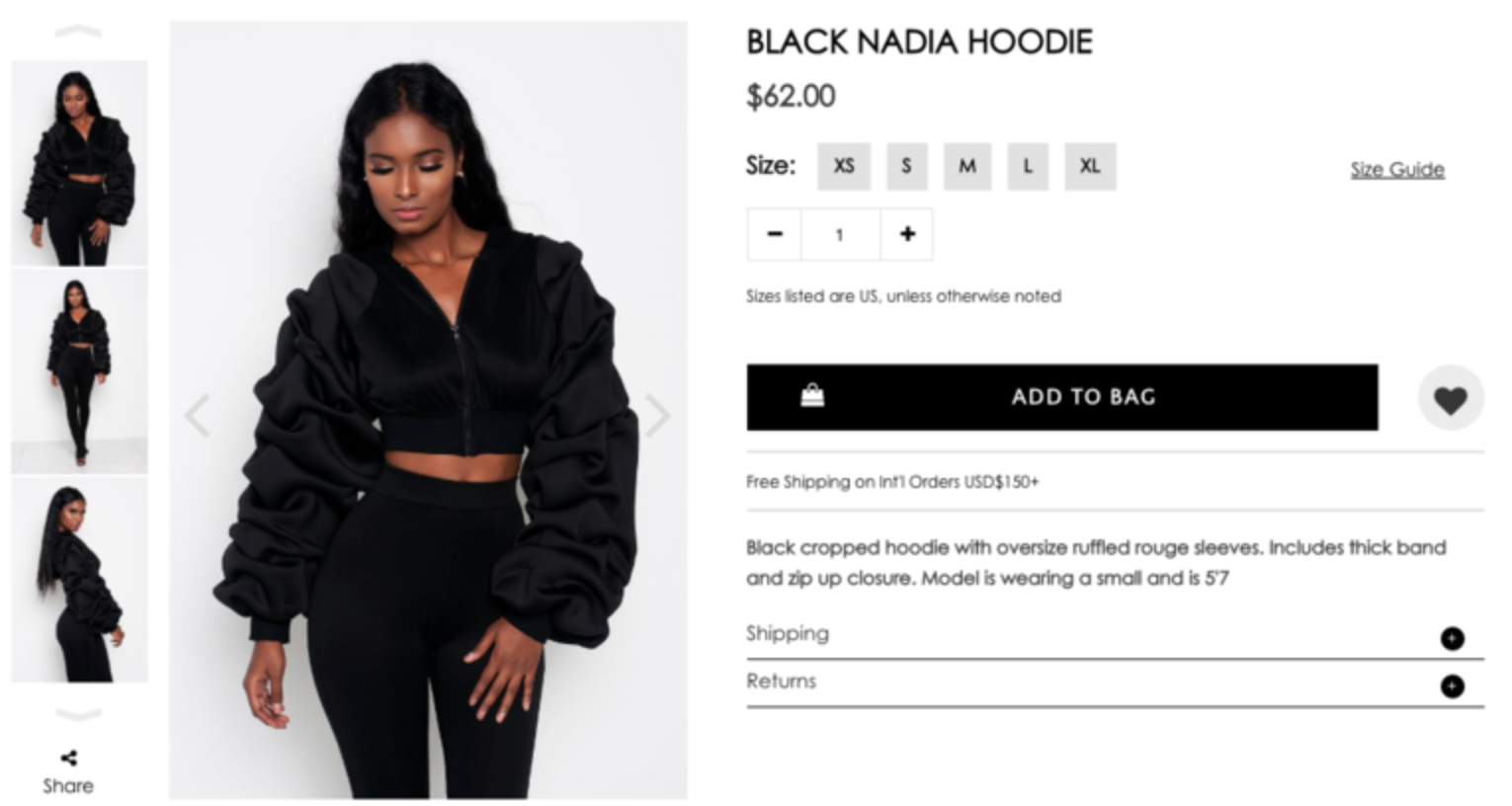

And here’s one more. Jai Nice and her brand Kloset Envy called out Fashion Nova for buying her Black Nadia Hoodie, copying the design, selling the knockoff on their website, and then having the audacity to return the original to the product to Nice. The audacity! Upon being called out, Fashion Nova blocked Nice and, a few months later, released another product that was eerily similar to Nice’s design.

This is just a few examples of Fashion Nova and the still prevalent racism in the industry. There’s so many more instances, but these are just the ones I wanted to focus on. So, long story short, please don’t buy anything from Fashion Nova. They’re trash.

I’m saying it again, as a white individual I will never experience racism in my life. I will never know what it feels like to be discriminated against, or lose opportunities or even my own life purely based on the colour of my skin. I need to acknowledge the privilege I have, based on my skin. The recent events; the murder of George Floyd and subsequent violence instigated by police during protests are incredibly intense, and in time will be catalysts for (hopefully) a better future. These events, even as horrific as they are, have inspired everyone (myself included) to stand up and stand with everyone to inform others and make a change. All I can do is to help others be aware of brands that have evidence of racism in any aspect of their business operation. If that’s what I can do, to do my bit, then I most definitely will.